Differences Between Push and Pull

Last updated: 2024-12-18 16:06:29

Differences Between Push and Pull

Last updated: 2024-12-18 16:06:29

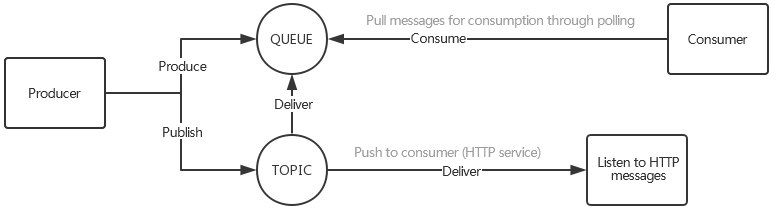

Push model: when a message sent by the producer arrives at the server, the server will immediately deliver it to the consumer.

Pull model: the server does not process the received messages; instead, it only waits for the consumer to actively read them from it, that is, the consumer needs to "pull" messages.

Scenario 1. Fast producer and slow consumer

If the producer is faster than the consumer, there will be two possibilities: the efficiency of the producer itself is higher than that of the consumer (for example, the business logic of message processing on the consumer side may be very complicated or involve disk, network, and other I/O operations); message consumption fails or is hindered in a short time due to failure of the consumer.

In the push model, the server cannot know the current status of the consumer, so it will continuously push the generated data. The consumer may have a heavier load and even crash under the two aforementioned circumstances (for example, the producer is Flume which collects a massive number of logs, and the consumer is HDFS + Hadoop which lags behind the producer in processing efficiency), unless it has an appropriate mechanism that can inform the server of its status.

In the pull model, this problem becomes much simpler. As the consumer actively pulls data from the server, it only needs to reduce its access frequency. For example, if the log collection business such as Flume on the frontend continuously generates messages to the CMQ instance that delivers messages to the backend, the efficiency of backend businesses such as data analysis may be lower than that of the producer.

Scenario 2. Real-timeness of messages

In the push model, once a message arrives at the server, the server can immediately push it to the consumer, which achieves a remarkable real-timeness. In the pull model, in order not to put pressure on the server (especially, when the data volume is insufficient, continuous polling will make no sense), it is important to control the consumer's polling interval, which will definitely compromise the real-timeness.

Scenario 3. Long polling in the pull model

The pull model has a problem where the consumer pulls messages proactively and thus cannot determine when exactly to pull the latest message. If the consumer successfully pulls a message, it can continue pulling the next one; otherwise, it needs to wait for a period of time to pull the message again.

As it is difficult to determine the waiting time period, you may use many dynamic pull interval adjustment algorithms. However, you still may encounter problems, as whether a message arrives is not determined by the consumer; for example, there may be 3,000 messages continuously arriving in 1 minute but no new message generated in the next several minutes or even hours.

CMQ provides an optimized mechanism called long polling to balance the advantages and disadvantages of the pull and push models. The basic principle is that when a consumer fails to pull a message, the failure will not be returned; instead, the connection will be in pending state to wait for the next message, and when the server receives a new message, it will activate the connection to return the latest message.

Scenario 4. Part or all of consumers in offline status

In a message queue system, the producer and consumer are completely decoupled from each other. When the producer sends messages, the consumer does not have to be online, and vice versa, which is exactly the main difference between message-based communication and RPC communication. There are many circumstances where a consumer is offline.

In case of accidental downtime or offline status of the consumer, the production by the producer will not be affected, and the consumer will continue to consume the last message when it goes back online; therefore, no message data will be lost. However, if the consumer is down for a long time or cannot be started again due to failures, there will be various issues to be addressed, such as whether the server needs to retain data for the consumer and how long the data should be retained.

In the push model, as it is impossible to predict whether the consumer will be down or offline temporarily or persistently, if all the historical messages since the crash are retained for the consumer, the data cannot be cleaned up even after all other consumers finish the consumption, and the queue will get increasingly longer over time. In this case, no matter whether the messages are stored temporarily in the memory or persistently on the disk (in systems using the push model, message queues are generally maintained in the memory for higher performance and real-timeness of push, which will be discussed in detail later), they will put huge pressure on the CMQ server and even affect the normal consumption of other consumers, especially when messages are produced at a high pace. However, if the data is not retained, it may be lost when the consumer is restarted.

A compromise is to set a timeout period for data in CMQ which will clean up the data when the consumer's downtime exceeds this threshold; however, the threshold is not easy to determine.

In the pull model, the situation is improved, as the server no longer cares about the consumer status; instead, it provides services only when the consumer actively communicates with it. The server does not make any guarantees about whether the consumer can consume the data in a timely manner (there is also a timeout period for cleanup).

Was this page helpful?

You can also Contact Sales or Submit a Ticket for help.

Yes

No

Feedback